A DESIGN APPROACH TO UNDERSTANDING SUPPLY CHAINS: Using Design Thinking for Agri-Food Net Zero Ambitions

Our initial goal at EATS was to understand opportunities for net zero and identify areas where sensing might reduce carbon emissions and improve transparency within sector supply chains. In order to gain an in-depth insight into the agri-food supply chains for the soft fruit and brewing sectors, we employed a combination of design and systems thinking. Our first step was to define the problem, review existing supply chain maps, and engage with the key stakeholders, from across the supply chains. Following on we conducted co-design workshops with participants including growers, agronomists, sector consultants, processors and distributors. We uncovered the intricacies of each sector supply chain to understand the full value chain and what constituted Net Zero scope 1, 2 and 3 for their business.

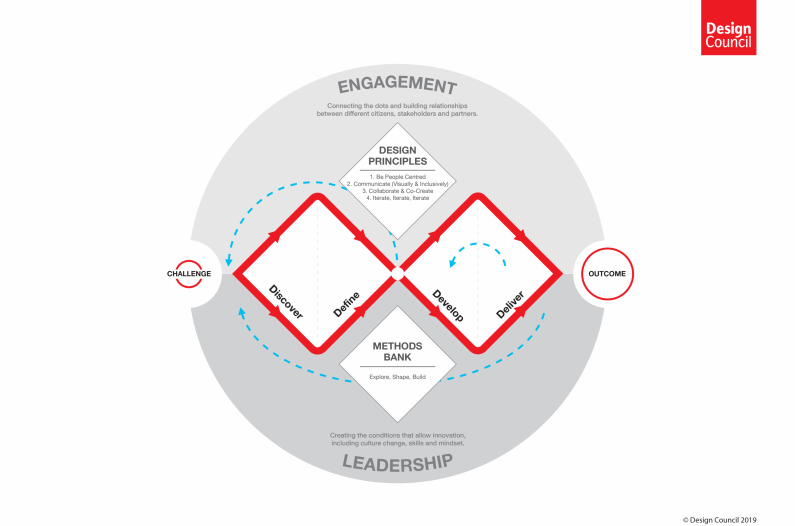

Design thinking is a user-centred approach to problem-solving often undertaken as an iterative non-linear process. It seeks to understand users, challenge assumptions, reframe problems and create the ‘right’ solutions to innovate through developing and testing prototypes. The application of design thinking together with systems thinking was key to tackling the complexity and interconnectedness inherent in the sectors and furthermore underpinned our co-design workshops which built on the Double Diamond framework (Design Council, 2021) (see figure 1).

These workshops aimed to:

- employ user-centred, interdisciplinary research to understand current practices and shape new solutions for environmentally sustainable food futures.

- investigate the motivations and responses of stakeholders and their use of such systems.

- establish current baselines for stakeholders involved in the ari-food processes, and collect environmental impact data in agri-food supply chains.

Our workshops, carried out by researchers from the University of Dundee, utilised a combination of design methods to support participants input. Workshops comprised of 4 key stages.

- Setting the Scene: Asking the question ‘How might we develop a better, more transparent supply chain.

- Supply Chain Analysis: Journey mapping the supply chain, mapping out technology and pinpointing what worked well, what needed improvement and where data and technology could fill a gap.

- Prioritising: Dissecting the maps to understand what the key problems are and asking how we can solve those problems.

- Visioning: Recording key events that affected participants, positively or negatively, and increased carbon emissions.

Findings & Next Steps

Over a number of workshops, we mapped the sector supply chains to identify the various actors, resources, and flows of materials, energy, and information. Participants shared their experiences, and we were able to determine the key areas where sensors should be deployed to gather data. Design thinking methods allowed us to investigate the numerous supply chain problems, including the environmental impact of the various processes involved, and distill these issues to those which matter. At the conclusion of the workshops, the problems highlighted all fell within net zero definition of scope one, that is related to greenhouse gas emissions that the company controls directly. These included cleaning, boiling and in-house packing processes in brewing, and crop growing conditions in soft fruits i.e. monitoring fertiliser use, humidity, water and polytunnel conditions. Brewers and growers shared a need for data that would enable them to make informed decisions to allow for supply chain changes that could not only reduce carbon emissions but also reduce costs and influence behaviour change. Our workshops allowed us to identify the key leverage points and interventions that could help to decarbonize the supply chain. Our next step is to conduct visits, to design protocols and strategies for sensor deployment, and conduct observation of human decision-making in action for problem areas highlighted in our initial co-design workshops.

Insights

- Our sector supply chain maps were not readily available or comparable, leaving knowledge gaps. As a result, we initiated our co-design process by validating maps with participants. This provided an opportunity to explore bespoke maps for participants.

- Our Methods allowed us to begin by capturing broad insights and in doing so enabled participants to get into the right mindset from the start before narrowing down ideas for the issue that was most pressing for them.

- As a result of our visioning session at the end of each workshop, we were able to spark further discussion and come up with real-world stories that left us with a much stronger sense of purpose. Several of the outcomes tell important individual stories of extreme events likely to impact these industries in the coming years, which we will explore further.